By Molly McPhillips, Touchstone Intern

Carolyn Marshall Wright dropping off her piece My Grandmother’s Bowl to curator Lenny Campello

The art scene in D.C is full of national museums displaying works that appear on art curriculums around the world. In all of this historical and culturally significant art, DC is missing a large piece of the art world from its very own community. The lack of artists from the city within these museums and institutions is a problem that has gained more attention in the last decade. Lenny Campello, the curator of the Women Artists of the DMV show, has called again and again for more representation of the brilliant artists of the area to be showcased in museums or limited time exhibits. When no one seemed to be making a change, he decided to do it himself.

In 16 locations across the DMV over 400 women are being given the chance to display their art, including Touchstone artists Veronica Barker-Barzel, Sue Canuteson, Janathel Shaw, Anne Stine, Rosa Vera, Gale Wallar, and Carolyn Marshall Wright. All of them have approached the show with their unique styles and goals, showing how diverse even such a small selection of this exhibit is.

Las Comadres IV by Rosa Vera

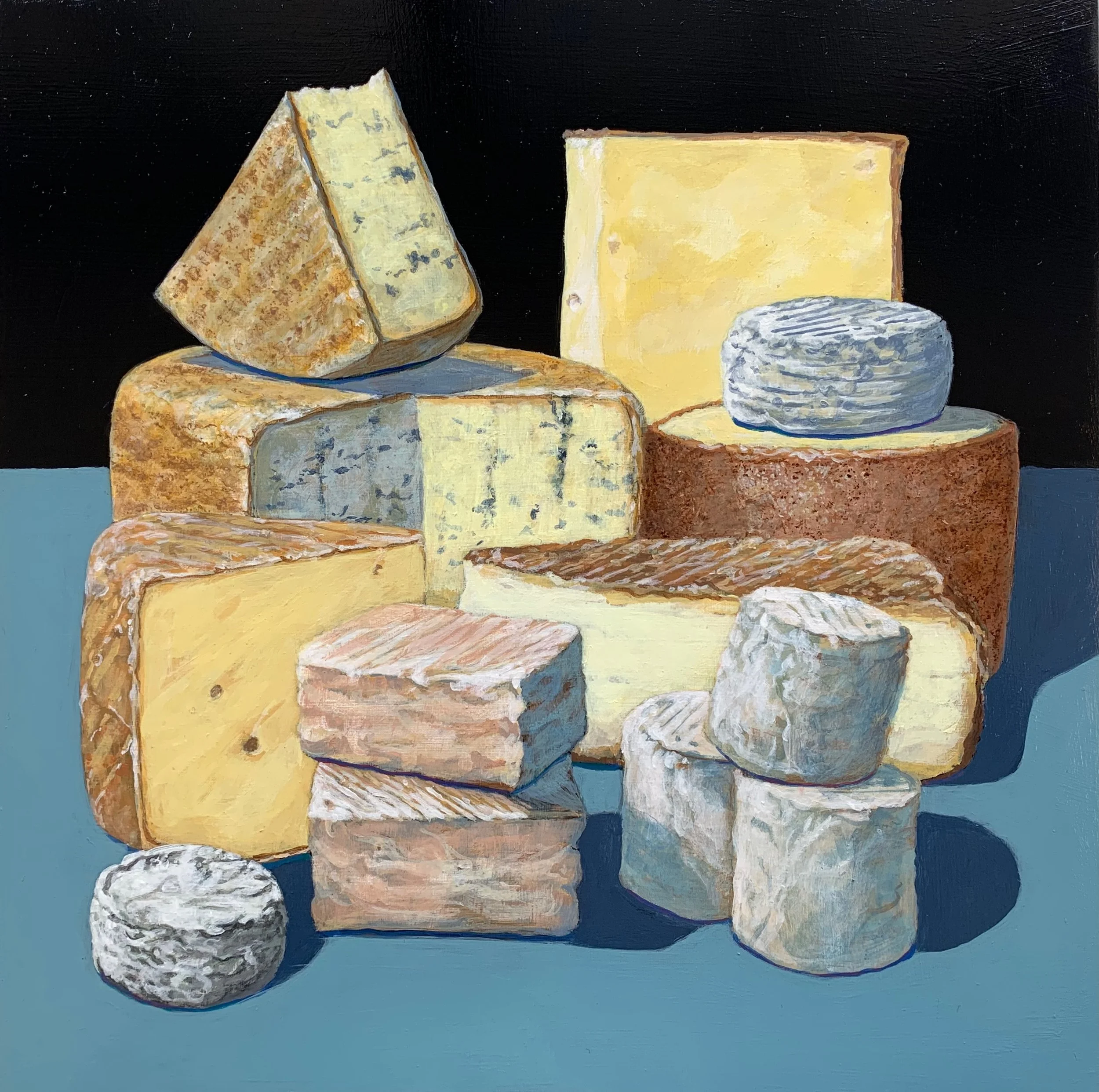

Fleur de Sologne and Others by Gale Wallar

Vera’s work is an example of leaning more into the feminine element of the show and her own Latin background—a piece that brings light to the problem of feminicide all around the world, but especially within the Latin community. She will focus on this topic in her upcoming solo exhibition, Resiliencia, at Touchstone Gallery (December 11, 2025 - January 11, 2026).

Some of the artists have gone in an opposite direction, showing off their interests as a creator. Canuteson’s Patterns at Play is much more lighthearted and when asked what she would like viewers to get out of it Canuteson says “maybe just a smile and the desire to look closer at how the work was made.”

Wright has submitted a still life of a bowl, called My Grandmother’s Bowl, bringing lots of ties to her fond family memories, hoping to create the beginning of a story with her art.

The scope of this show is huge, as seen in the comparisons above. In the art community there is still a disparity between artists who are men and those who are not, which is no secret. In putting this show together Campello decided to take that extra step and highlight all the women artist talent that does not get the attention it should. Through this show he hopes that major institutions like the Smithsonian may begin to take local artists into their spaces more and help promote artists from their own community. This show has already gained a large amount of publicity, as well as the attention of some politicians in the city, which Campello has used to be able to open up discussions about DMV arts.

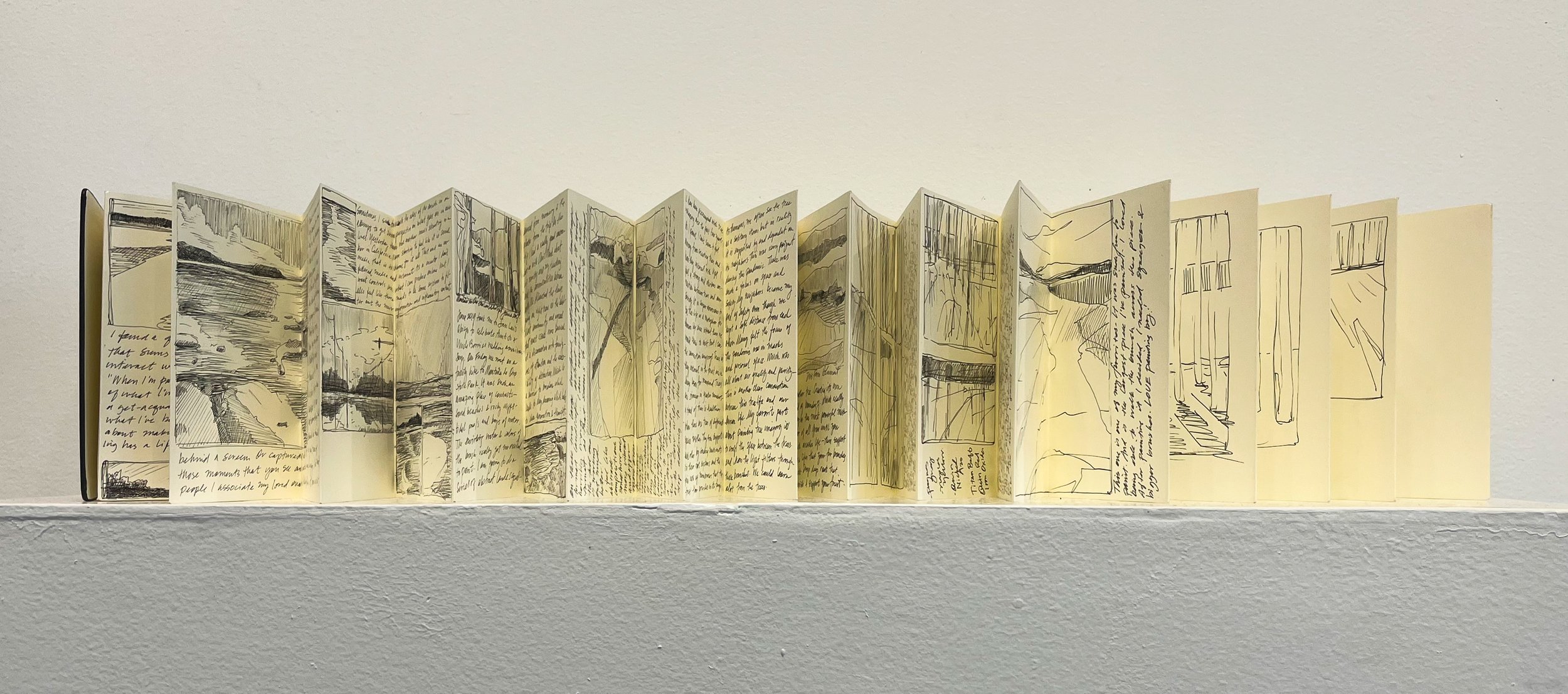

Patterns at Play by Sue Canuteson

Grief for Philando (Castille) by Janathel Shaw

When asking the Touchstone artists to explain the process of being a part of a show like this, they all commented on how easy it was. Allowing this show to be accessible for artists is certainly a large part as to how it has grown to the mega-show that it has become. Wright noted to me how easy the process was, saying she just had to reach out to Campello, and he provided some size requirements, having no lengthy interview process that can often be attached to these shows. With so many locations across the DMV Campello is also bringing contemporary art shows out to people who do not normally have access to this, not living in D.C.

Women Artists of the DMV is on view at various locations, some until January of 2026. The artists participating bring pieces of themselves within the art and create a sense of personability and community within these art spaces, inviting people to recognize what the region has to offer. The Touchstone artists included in the exhibition are a part of something much larger than a show—they are part of a journey to bring local arts to the spotlight and create a larger focus on the art created by women.

Find Touchstone artists in the following shows and locations:

Rosa Vera - Montpelier Art Center until Nov. 3

Veronica Barker-Barzel - Artists & Makers Studio until Oct. 29

Carolyn Wright - ACM Gallery at Children’s National Hospital until Jan. 9

Sue Canuteson – McLean Projects for the Arts until Nov. 1

Anne Stine – Melissa Ichiuji Studio Gallery until Dec. 7