Intern Emma Cunningham-Bradshaw interviewed Touchstone member artist Amy Sabrin about her ‘In Provence’ watercolor collection and her trips to an artist residency in the Provence region of France that inspired it. Amy fondly recalls the fun shapes of the trees, the pervading smell of lavender, and the vivid colors that make you think of artists such as Cézanne and Van Gogh who painted scenes of Provence as realists rather than impressionists. Emma followed in Amy’s footsteps, visiting many of her favorite places in Provence while endeavoring to capture elements of the environment that Amy was so enamored with.

The Zoom waiting room closes and up pops Amy Sabrin in a pale green shirt with one of her own watercolor paintings as the background: blue-purple trees in the region of Provence, France, casting shadows over a golden yellow field. Amy thought it appropriate to showcase this image since today we are speaking about her collection ‘In Provence’ and what inspired it. Starting in 2009 and continuing for eight non-consecutive years until before the pandemic, Amy went to a hamlet in the Luberon National Park called les Bassacs. There, for two weeks in the summer she attended Arts in Provence, a program started by two British artists who had lived in Provence for years. When Amy began going to Provence, she was still a full-time lawyer. “I didn’t have much time to paint when I wasn’t there. So, I just wanted to paint every hour I could.”

Under the Olives

The primary activity every day at Arts in Provence was ‘plein-air’ painting which is, most simply, when one paints outdoors. ‘Plein-air’, literally ‘open air’, is a practice that emerged in the 19th century in France with the invention of tin paint tubes. This enabled artists to travel with ready-mixed paints. ‘Plein-air’ painting fueled the Impressionist movement with artists such as Monet and Renoir endeavoring to capture the changes in the environment on a canvas. Amy says of her summers in Provence, “lavender was in bloom, every day you would go out and paint plein-air in this new, beautiful location and then you had art instruction in the afternoon, art critique and wonderful meals, homemade on-site with all the fresh local food and wine. It’s just an unbelievable experience in a beautiful place so I kept going back, and that’s what inspired all these paintings.” I ask Amy about what she thinks drew such famous artists, and continues to draw artists to Provence today. She believes it is the light and rural scenery. “When I think of Provence, I think of Van Gogh and Cézanne. When you walk into these pine forests, they look just like a Cezanne painting! You think his painting is made up, it’s actually more realist than you think it is… those colors, especially the orange and the green. It’s just such a pleasant environment.”

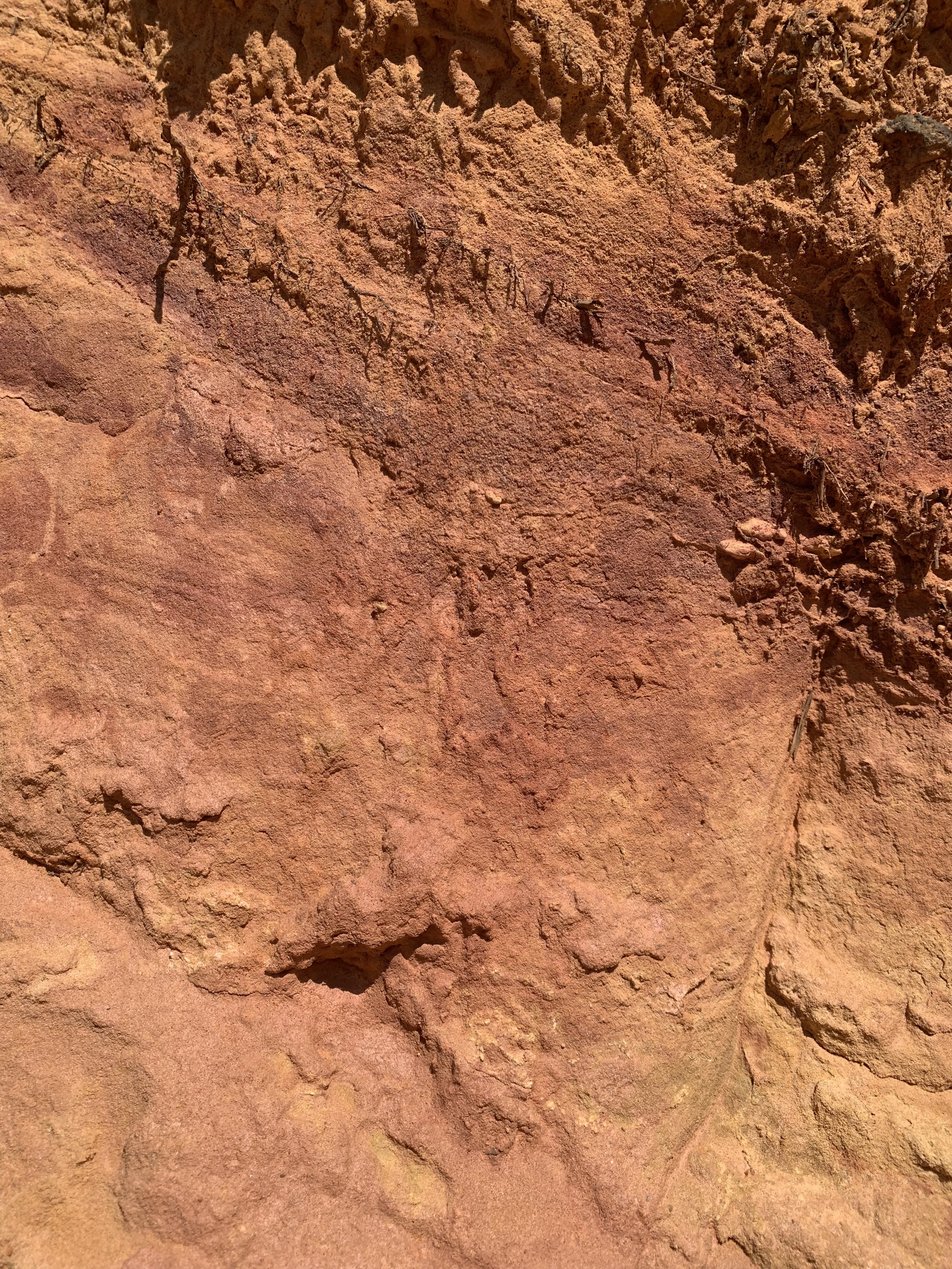

This vibrant orange is best showcased in the ochre quarries of the Luberon Valley. I visited one of these quarries named ‘Le Colorado Provençal’ because of its startling similarity to the American Southwest’s colors and rock formations. Indeed, the smell, dry heat and colors all reminded me of Colorado or New Mexico. The ground beneath as I walk up the mountain, on a path between fragrant pine trees, is red clay. As the rock formations come into view, one sees a continuum of color, from light pink, to yellows, bright oranges and reds. This land was mined for paint pigments for almost two centuries, and is now protected territory where people like myself and Amy can admire the land. This type of land is something I never fathomed seeing outside the US. One thing that reminded me I was in Provence while on that hike was seeing the lavender fields atop the mountain, blowing in the breeze and buzzing with bees.

Amy’s plein-air painting at the ochre quarry

However, the vibrant colors in the ochre quarries are anomalies with regard to the Provence landscape. The colors of the vegetation oscillate between yellows and pale greens. Much of Provence is wheat fields, and so that golden color of grain is ubiquitous. The ground is sandy both in color and texture. It is a very dry environment, though there are lush milieus like shaded gardens and vineyards—Provence is famous for its rosé. Out in the open, unshielded by shade, the heat is quite relentless, particularly in the afternoon when everything slows down. At that time, most businesses close and people take their daily respite from the toils of the day. Arts in Provence also abided by this tradition. After finishing the daily art lesson and of course a sumptuous meal, the artists were free to do as they wished. Amy said most often they would sketch or paint in the environs of the school, either individually or as a group. “There are these beautiful undulating vineyards and lavender fields within a very short walk of where we stayed and so that was a frequent attraction.” When I visited Les Bassacs, I walked on a path that continued beyond the village. I focused on the trees rising on either side and their shadows, criss-crossing on the ground below. I imagined Amy would have painted there, and I’m sure she did. She said of Les Bassacs, “that time of year you can be outside until 10 at night; it’s still light. The sunsets, the sunrises are gorgeous. Where we stayed there are many teeny weeny villages and they’re all perched on the side of the valley. The art school was on one side, and if you sat on the patio overlooking the valley, as it got dark, the lights would come on all over. It was just magical.”

Shadow Play, painted plein-air in Les Bassacs

One can discern Amy’s love of light, color and shape in her ‘In Provence’ paintings: shadows of trees cutting luminous paths, flame-red tomatoes in market baskets, a sinuous black cat on a pastel window sill. Amy painted exclusively in watercolors when she was there. “One thing I really like about watercolors is that they’re so transparent and luminous and the light bounces through them, and that is consistent with the environment there. From a technical point of view, if you’re working fast, watercolor dries fast, since it’s a very dry environment.” She found the trees in Provence particularly appealing. “The trees just have the most fun shapes and they make the most fun negative shapes, and their leaves are this interesting silvery color. It took me like two years to figure out how to mix that color. The sun comes under them and they cast these cool shadows.”

Market Day, Apt

The coloring of the towns in Provence reflect the natural environment: dry with toned down versions of every color. One sees shutters the same purple-gray as lavender fields and walls of orange hues (some painted with pigments from the ochre quarries). Many of the towns in Provence were founded prior to the 15th century, including Saint-Saturnin-lès-Apt, one of Amy’s favorite towns. At the highest point of the town, there are well-preserved ruins of a medieval fortress and several cypress trees (perhaps Van Gogh’s favorite tree, as seen in his paintings) as well as a still-operating church dating to the 11th century. You are also surrounded by a stunning vista of the Luberon Valley and look down to see all the clay-shingled houses of the town proper. There, you walk through narrow sloping streets, stumble upon arched passageways, see bushy vines shrouding ornate doors and all those classic Provence colors.

Dreaming of St. Sat

While Amy has painted scenes from several countries, there are only two places that she is most drawn to: coastal areas in the US (she is calling me from Bethany Beach, Delaware) and Provence. She sees the commonality of these two areas in their colors and bright light. These are environments she’s spent a lot of time observing, practicing mixing the colors she perceives around her. Years of immersion in Provence made her very familiar with the land. “I went so many years in a row, that I could almost paint with my eyes closed, thinking of the sounds, the breeze, the sunlight.” She even cultivated relationships with market vendors who she would see year after year. “In the eight years I was there, the same vendors were always in the same place. I remembered the vendors and they would remember me.”

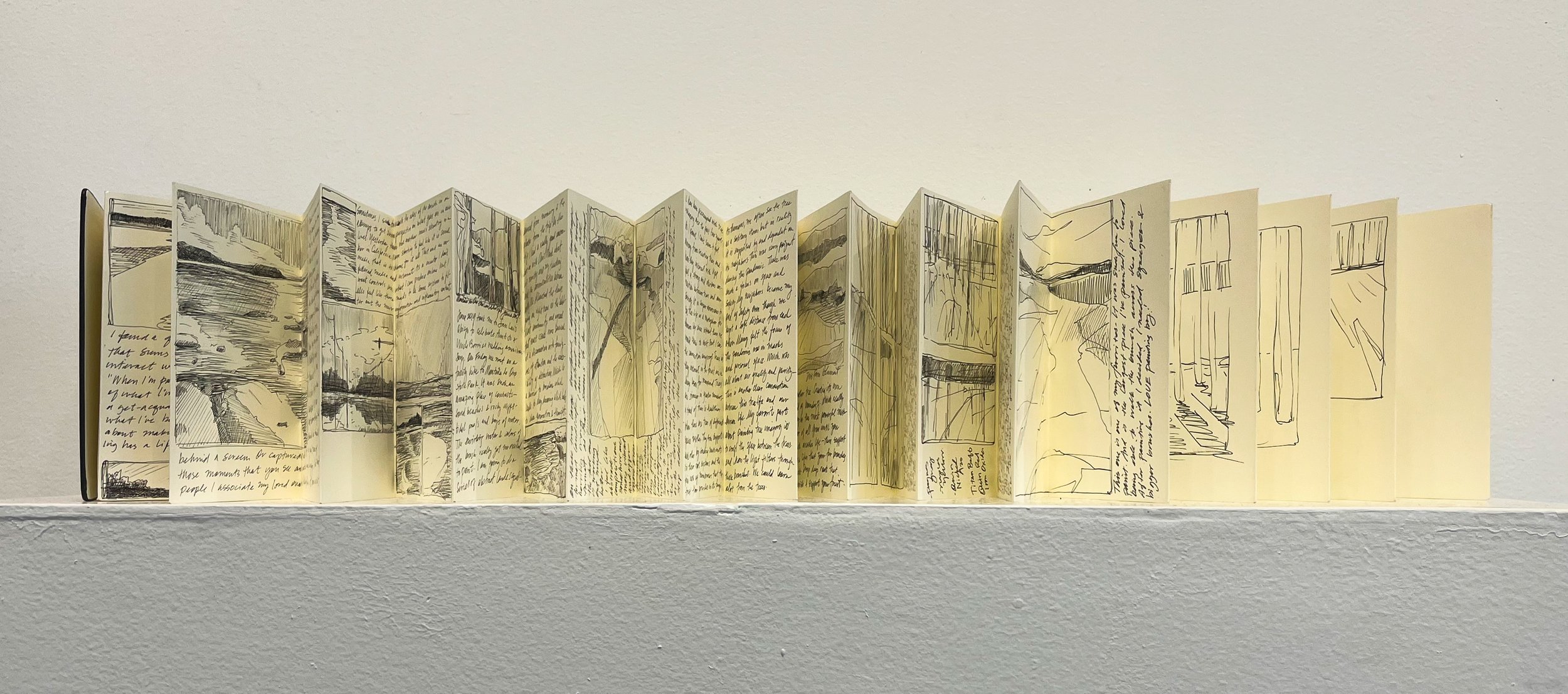

About half of the paintings in the ‘In Provence’ collection were painted plein-air in France, while others were inspired by the memories and photos of her surroundings. Arts in Provence has not operated since the pandemic. Yet, even though Amy hasn’t been to Provence in several years, the sense of the environment is embedded within her. “I look at the paintings I did in Provence and I can remember what it felt like when I painted it, when I was in that place.”