Slow Walking, Michael A. Lang’s June 2019 show at Touchstone Gallery, invites the viewer to join him in wandering the streets of New York and visiting small towns in Sicily, during Easter week. Lang is a skilled observer of the human condition. The candid pictures display a keen sense of composition and a surprising intimacy. “I want people to have a chance to see what I see, to see things as I see them and to experience the feeling that I had,” he says.

Lang is a street photographer who describes much of his work as social documentary photography. “Street photography is when I go to New York and just walk around the streets taking pictures of things I see. There is no theme to it, except that these are the streets of New York,” he says.

The Sicily pictures were photographed the same way. What unites them as a social documentary is the theme of Easter week and the importance of the Easter celebration to people in the small towns of Sicily. “It is their main holiday of the year, and they are very serious and intense about it,” Lang says. “I really admired that, the relation of the celebration to their religious beliefs.”

How Does He Do That?

To get shots like this, Lang appears non-threatening, almost invisible, to his subjects.

But how, a viewer might ask, is he able to capture people in such un-posed, unguarded moments? “The picture has to be seen before you pick up the camera,” he says. “I see it, I pick up the camera, and I take a picture. It’s a quick, instantaneous thing.” Lang never asks permission to photograph someone. “If you get into that kind of interaction with people, you don’t get good pictures.” Since he photographs in public places, he does not have to get a release from the subjects or permission from the proprietors of public establishments, such as bars.

Lang has two approaches to getting the shots he wants. Often, he will start a conversation with a potential subject. One of the photos in the exhibit shows a man on a motorized scooter with a sign asking for money so he can travel to Texas. “I come up to him on the street, and I stop. I can tell that he’s a guy I can talk to. I ask him some questions. He replies. We are having a natural interaction. He’s not posing. He’s just doing things. We’re talking. And I lift the camera, and I take a picture.”

Other times, Lang is walking on the street and just sees something that interests him. Again, he picks up the camera and takes a picture. “You have to be a combination of non-threatening and invisible,” he says. “You are there. People can see you, but you are not interfering with them.” Only twice in his career have people asked Lang not to photograph them, and he complied. First, they were both drug dealers. More importantly, “A picture of somebody who doesn’t want to be photographed will never be a good picture, and it’s not worth trying. This isn’t a tabloid or paparazzi operation,” he says. “Otherwise, you just have to know how to interact with the scene. It’s not something that can be learned. You must be comfortable with people and your surroundings.”

The Art Part

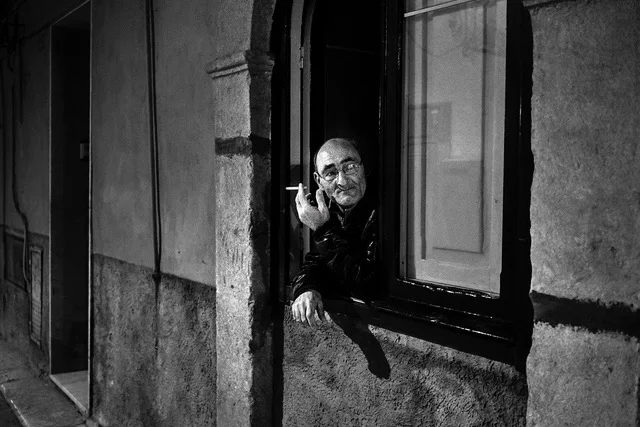

The tonality of this image directs the viewer’s attention to Lang’s subject.

The images are the result of candid photography on the street, but the work is also an art form. “The pictures have to be inviting to look at, and they have to be well-printed,” he says. He works primarily in black and white and now processes all of his work digitally. “As my technique, available technology, inks and software developed, I found that I was able to produce prints for exhibition that were equal to what I was doing in the darkroom,” he says. “My approach when I am doing digital is not to take advantage of the tricks you can use, but to make it an extension of darkroom work.” He takes great care with papers and inks, and he gives particular attention to tonalities, or the range of shades from light to dark. Even experienced photographers often cannot tell that Lang’s prints were not printed in the darkroom.

For example, the signature piece in Slow Walking shows a gentleman leaning out a window while smoking a cigarette. Lang adjusted the original lighting so that the background has gradation from dark at the left and right edges to light approaching the figure. “When you see the picture, your eye doesn’t wander. It goes right to the man,” Lang says. “There is a message in the picture, and that is what your attention and eye should focus on. The tonalities cannot be just gray and flat throughout. There has to be a good range of darks to lights. That is true of all the pictures in the show.”

Photography on the Edge

Lang is often attracted to what many would consider to be the edgier side of life. It started when he was about 14. His parents had acquired high-quality cameras and photography equipment before abandoning the hobby. One day he took a Leica camera out of the closet and started shooting. One of the photos won a trophy in the All Maryland Salon, a prestigious competition for experienced photographers. With his mother’s encouragement, he joined a camera club. The other members, primarily adult men, mentored him and taught him the fundamentals. However, their approach to photography was quite formal, and he wanted to create something different.

Eventually an older friend took him to a pool room in Baltimore. “I was fascinated by the atmosphere there. Instead of spending my time shooting pool, I spent the time taking pictures,” he said. “I made only proof prints of them when I shot them, but I kept the negatives with me as I traveled.” About 40 years later, toward the end of a successful career as a biophysicist, he returned to photography. He used the pool room pictures to create a photographic essay that became his first solo show at Touchstone Gallery. During that time, he revisited the pool room. It had moved to a new location, but it was still operated by the same person and inhabited by some of the same people he knew in 1957. With a grant from the State of Maryland he obtained oral histories of what Baltimore was like in the mid-50s and is currently working on a book on the subject to be published on line .

Lang’s work often humanizes people that might not otherwise be seen or accepted. “I do edgier themes, because I am intrigued by people who are different than I am and have another way of looking at things,” Lang says. “I was not a person who hung out all the time in pool rooms.” He is not a drag queen, either, but the D.C. drag scene became the subject of another photographic essay. “Different points of view and different ideas fascinate me. I express my observations and interactions with others through photography instead of writing or talking.”

He has also produced social documentaries on the hill tribes of Northern Thailand; Jackson, Mississippi’s Farish Street, once a thriving center of African-American business and culture, now a deteriorating neighborhood; and the original slow walking series, 2017’s Slow Walking in New York. “I do not want to bring people down with my photographs. I feel good about these people and these experiences,” he says.

Seeing More

Street photographer Michael A. Lang

Lang might well have chosen photography rather than science as a career had it not been for paraplegia resulting from childhood polio. He now walks very slowly, hence the title Slow Walking. “It takes me more time, so I have more time to look and see,” he says. “Therefore, I can convey to you the things I see that you might not: a composition of cymbals, the expression on the face of a trumpet player, the feeling of relating to the music of a musician at Birdland, all of these things. If I can bring out the feeling that I see by taking a little more time and looking a little more closely, I have achieved my purpose.”

Lang’s wife Anita says that he does not take photographs because he wants to, but because he has to. He agrees. “This is how I communicate. That’s why I do it,” he says. A walk through his world communicates that we should all slow down, seek out the different and see beauty where we have not seen it before.

###