By Alicia Perkovich, Gallery Assistant Intern & Heat Exhibition Specialist

In our last blog post, we provided an overview of numerous ways artists have depicted heat in art. Today, we’ll be focusing on perhaps the most common form of this theme—summer.

18th and 19th century French artists showed the beauty of summer heat in their paintings. Known as Impressionists, because critics of the time felt that their work looked more like impressions than completed works, these artists created landscapes of their changing environments which favored natural light, as well as bold colors and brushstrokes. These artists were radical for their time as they didn’t paint inside a studio, but in nature. They were also radical for using short strokes of unblended color, as well as using vibrant palettes where color, rather than incorporating white and black, made up highlights and shadows.

Claude Monet Haystacks

For example, in Claude Monet’s Haystacks series, where he painted the same haystacks at different seasons, times of day, and angles— to show how light can transform a singular subject— the vibrant yellows and oranges of End of Summer, Morning help us feel the sunlight’s warmth, while pale lilac tons in the background show the bounty of the season. Monet’s brushstrokes highlight the hay’s texture while providing a foundation for the light as well as shadows.

Berthe Morisot Summer’s Day

Berthe Morisot’s Summer’s Day, on the other hand, shows how the French middle class can enjoy the leisure of summer. In a calm pond surrounded by trees and grass, two elegant, and assumedly wealthy, women are seated in a row boat, with the left-hand figure looking at ducks in the pond, and the central figure staring forward with an umbrella on her lap. While the subject appears tranquil, Morisot’s technique is quite dynamic, due to her zig-zag brushstrokes which showcase light reflecting from the water, as well as her color palette that takes advantage of new synthetic paints, such as cerulean blue and cadmium yellow.

Throughout the century, these artists would escape to the South of France during the summer— not only for a sea-side vacation but to experience a region for new, inspiring landscapes. While much of Impressionists work had been focused on how modernity has altered natural landscapes or attention to rural respited amidst urbanization, the French Riviera provided a new oasis of fishing towns, coastal landscapes, and saturated colors for artists to depict. Staple names of the Impressionist movement, such as Claude Monet and Pierre-Auguste Renoir, therefore sang the region’s artistic praises. As time went on, artists such as Henri Matisse— who took on a new movement known as Fauvism— made these travels to greater extents, finding remote coastal towns that led to vivacious, expressive paintings.

Left: James Francis Cropsey Summer Landscape; Right: Henri Matisse Seated Woman, Back Turned to the Open Window

Landscape painting was also formative to American artistic tradition. As America forcibly expanded westward under the ideology of Manifest Destiny, landscape paintings that depicted a vast, unspoiled wilderness romanticized the American landscape. This style was most official in the Hudson River Valley School, which consisted of a group of landscape painters centered in New York. Their paintings were grand in scale as well as subject, depicting panoramic natural landmarks with dramatic light, and features that expressed a renewal in American identity and spirit. James Francis Cropsey’s Summer Landscape, for example, shows a shaded riverbank with a couple— miniscule in the landscape’s scale— enjoying the leisure and harmony of undisrupted nature.

Georgia O’Keefe My Front Yard, Sumer 1941

While painter Georgia O'Keeffe is best known for her enlarged paintings of flowers, she also has numerous landscapes of the New Mexican Desert, an area that became her artistic focus and home in the later portion of her career. A constant throughout her work, O’Keeffe injects life into her subject with lush greens and warm peach tones, along with clearly defining the contours and elevation of the mountain.

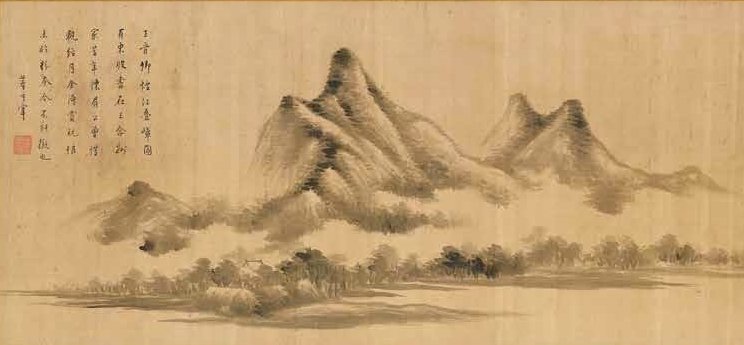

Summer landscapes, however, aren’t confined to European or American art. By the Tang dynasty (619-908 AD), Chinese art championed the genre of landscape painting through ink on paper scrolls. Almost a century later, under the Ming dynasty, there were two prominent styles of landscape painting: the depiction of gardens and orderly landscapes which symbolized the order of the state, and literati painters such as Dong Qichang who depicted landscapes as a form of self-expression.

Dong Qichang, Landscape and Calligraphy

Asian landscapes did, however, influence modern European artists. In a phenomenon known as “Japonisme,” artists such as Edgar Degas and Vincent Van Gogh took inspiration from Japanese landscape paintings brought to Europe upon the country’s reopening of trade in 1853; While not a landscape artist, Degas often used extreme horizontal compositions with asymmetrical compositions and noticeable negative space, while the strong lines and contrasting colors of Japanese woodcuts influenced Van Gogh’s depiction of his local landscapes.

Following this brief historical overview, let’s give attention to how artists at Touchstone have continued the tradition of idyllic summer depictions.

Elaine Florimonte The Opposite Side I

Elaine Florimonte The Opposite Side II

Elaine Florimonte’s duo of The Opposite Side I and The Opposite Side II follow this tradition. The acrylic collages depict opposite sides of the same river, using distinct strokes in white to visualize sunlight, and dark blues to evoke the reflection of surrounding trees on the water. This attention to natural light is central to Florimonte’s identity as an artist, per the artist statement on her website.

Rosemary Luckett Daydreaming in the Garden

Also of note from the July member show is Rosemary Luckett’s Daydreaming in the Garden— a collaged portrait of a figure staring off to their left side. The gaze appears peaceful, but perhaps not fully satisfied. With a flower in their hair, sheet music as the backing for the figure’s mouth, a jewelry chain lining the hair, an upcycled bottle cap for a necklace, Luckett’s work reads as whimsical, picturesque, and using elements of nature to provide a harmonious collage which reminds us of the leisures of summer.

Linda Bankerd White Cap

Lastly, Linda Bankerd’s White Cap and Marcia Coppel’s Just Say Cheese are both paintings which, similarly to French impressionists, depict the leisured actions of people in summer locations. Coppel’s painting shows a collection of people at the beach, confidently posed in swimsuits, with beach chairs and umbrellas. Bankerd’s painting focuses on one figure sitting and reading at the beach. While the effortless joy and relaxation is similar to Impressionist works we’ve discussed, our Touchstone artists still have a distinct style through their color choices. For example, Coppel’s use of blues and greens for skin color make her work appear more playful, finding unconventional ways to visualize the joy of summer activities.

Marcia Coppel Just Say Cheese

In our upcoming blog post, we’ll discuss how climate change has altered the way contemporary artists view summer heat. To view any of our mentioned works visit the HEAT member show, open Wednesday through Sunday from 12:00 pm -5:00 pm until July 31.